‘The common folk… live on songs’: Reflections on Hilary Mantel’s Mirror and the Light.

In this blog, I wanted to share some of my musings on the role of song in Hilary Mantel’s Mirror and the Light, which I chatted about earlier this Summer as part of ‘Cardiff BookTalk’. For anyone that would prefer to listen to the ‘live version’ (and the fantastic presentations from my co-panellists, Catherine Fletcher and Sophie Coulombeau) please do feel free to watch the video on YouTube.

‘The common folk of England live on songs and tales and alehouse jokes’, observes Mantel aptly in the final instalment of her monumental trilogy on Thomas Cromwell: The Mirror and the Light. And despite this being a novel ostensibly about the most powerful figures in Henrician England, some of the genius of Mantel’s prose is in recreating the past across the social spectrum and in bringing ‘common folk’ characters about which historically we know nothing, to the very forefront of her text. This is exemplified, for example, when we hear the agonised voice of Christophe – Cromwell’s loyal servant – screaming from within the press of the crowds that amassed to witness the Earl of Essex’s execution (p.873):

Henry King of England, I Christophe Cremuel, curse you. The Holy Ghost curses you. Your own mother curses you. I hope a leper spits on you. I hope your whore has the pox. I hope you go to sea in a boat with a hole in it. I hope the waters of your heart rise up and spout down your nose. May you fall under a cart. May rot rise up from your heels to your head, going slowly, so you take seven years to die. May God squash you. May Hell gape.

Alongside powerful moments like this, one of the most interesting ways Mantel brings ‘common folk’ to life, I think, is through the popular songs that permeate the entirety of Mantel’s trilogy, and which play a pivotal role in The Mirror and the Light. Here I want to draw attention to the ways that Mantel uses balladry in her narrative to illuminate the lives of ordinary people, and then highlight the ways that these popular songs are used to underline Cromwell’s complicated social status – vital to her portrayal of his character – as a man living in two worlds, lifted up from his base level, from one of the ‘common folk’, and thrust into the world of the nobility. The conflicting elements of his character is something that underpins the novels, and this portrayal is emphasised by popular songs.

The first stirrings of what was later known as the Pilgrimage of Grace began in the early Autumn of 1536. Rumours spread widely that the king had died, that Cromwell was planning to demolish all of the parish churches, that taxes were to increase to the highest levels ever seen, and that widespread famine was imminent. Rumours circulated during this period in large part due to popular song and broadside balladry, where information was bellowed and sung aloud by balladeers and news-sellers. Individuals would buy broadsheets for less than a penny, and these were then pasted up on the walls of taverns and people’s homes to be sung aloud to those that couldn’t read them. It has been estimated that by the second half of the sixteenth century it is likely that at least 600,000 ballads were circulating, but this number could have been as high as 3 or 4 million.

Mantel describes the stirrings in Lincolnshire (pp.296-7):

Last night they stole the watchman’s rattle, and knocked the watchman down. Now they go rattling through the streets, proclaiming the ballad of Worse-was-it-Never.’… ballads sung by our grandfathers need small adaptation now. We are taxed till we cry, we must live till we die, we be looted and swindled and cheated and dwindled… O Worse was it Never!

Farmers bolt their grain stores. The magistrates are alert. Burgers withdraw indoors, securing their warehouses. In the square some rascal sways on top of a husting, viewing the rural troops as they roll in. ‘Pledge yourselves to me – Captain Poverty is my name’. The bell-ringers, elbowed and threatened, tumble into the parish church and ring the bells backward. At this signal, the world turns upside down.

Worse was it never is the first ballad referred to specifically by name in Mantel’s text. Also known as ‘the maner of the world nowadays’, this is a text that supposedly started life as verses written by the poet John Skelton who died in 1529. It was later printed as a ballad, as this surviving undated broadsheet attests.

‘The Maner of the World nowadays’, Huntington Library, Britwell HEH 18348 [1562?]

This broadside’s particular role in stirring up the rebels in the Pilgrimage of Grace is not one that I am aware of, but it is easy to see why Mantel would make this suggestive connection. With its lament about England’s spiritual decay, such as attack on lollers – likely a reference to lollards, late medieval heretics who, among other things, promoted the gospel in English – as well as financial corruption, its themes are highly pertinent to the complaints of the Pilgrims. Ballads are known to have been widespread and played an important role in stirring the rebels into action, as a way for them to make exhortations alongside condemning Henry VIII’s advisors (p.323):

How is it some verse against Cromwell, sung in the street in Falmouth, is chanted next day in Chester? The further he travels from London, the stranger Cromwell gets. In Essex he is a scheming swindler, a blasphemer and renegade Jew. Spread him east to Lincoln and he is notorious for his knowledge of poisons. In the dales of Yorkshire he is a magus, with the stars and moon on his coat, while in Carlisle he is a ghoul who steals children and eats their hearts.

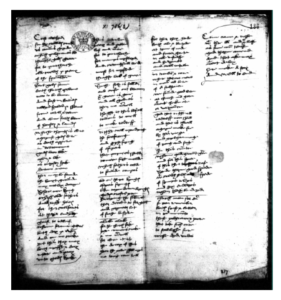

Widespread opposition to Cromwell was made starkly apparent during the Pilgrimage of Grace. A surviving contemporary ballad preserved in the state papers, (see below) linked Cromwell’s fiscal policies and imposition of new taxes, with the attacks on papal supremacy and dissolution of smaller religious houses. With thinly veiled references to Henry’s chief advisors – ‘Crim’ for Cromwell, ‘Cram’ for Cranmer, and ‘Rich’ to Richard Rich – seditious ballads like this circulated in the voices, hums, and whistles of the populace, as well as being written down and circulating in manuscript – memorialised by state informants like this one.

‘Salley Papers’, The National Archives, SP 1/108 f.184, 1536.

Despite this preservation on the page, in either print or manuscript, ballads were not static. Their meanings shifted based on the context and circumstance of their use and performance. As we heard, ‘Rebel ballads sung by our grandfathers need small adaptation now’, as Mantel situates Worse was it never as a pilgrim ballad. As well as shifting meanings based on time and place, ballad texts and melodies also often changed. Balladry was one of the most adaptable forms of the age. Multiple texts were composed to be sung to the same tune, this same tune sometimes developed different names, and multiple melodies could sometimes also be associated with the same text. Texts were also often circulated without a melody, as to its contemporaries the melody would have been obvious based on the text itself – but to our modern eyes and ears this association is lost. Unearthing these lost melodies is incredibly difficult for scholars – because even at the time, if the named melody for a ballad text didn’t fit the words perfectly, it was well known that words could then be left out or notes lengthened and shortened in order for it all to fit together. The adaptability of ballads, then, aided their elusiveness and their ephemerality. They inhabited a shared culture that crossed social and geographical boundaries, but at the same time struggled to be grasped. These characteristics of balladry, I think, are in many ways much like the character of Cromwell that Mantel has portrayed. In the final part of this blog I’d like to draw attention to examples of this.

My first example is from this pivotal part of the Mirror and the Light where we see for the first time, Cromwell’s explicit reach for royal power (p.510):

And you work too hard,’ Henry says: as if he were not the cause of the work. ‘If I die before my time, Crumb, you must …’

Do it, he thinks. Draw up a paper. Make me regent.

‘You must –’ Henry breaks off: he breathes in the green air. ‘So soft an evening,’ he says. ‘I wish summer might last for ever.’

He thinks, write it now. I will go back in the house and get paper. We can lean against a tree and make a draft.

‘Sir?’ he prompts him. ‘I must …?’

We can seal it later, he thinks.

Henry turns and gazes at him. ‘You must pray for me.’

They ride and hunt: Sunninghill, Easthampstead, Guildford. The king’s leg is better. He can make fifteen miles a day. In the mornings he hears Mass before he rides. In the evenings he tunes his lute and sings. He sends love tokens to his wife. Sometimes he talks about when he was young, about his brothers who have died. Then his spirits rally and he laughs and jokes like a good fellow among his friends.

The moment lost, the narrative continues and Henry sings a ditty that Cromwell remembers his father used to sing, O peace, ye make me spill my ale. This is the second ballad Mantel refers to explicitly by name in her text, and here Cromwell struggles to remember when he has heard another version of this song, ‘Where did he hear that? No women are assaulted in the king’s version, and the words are cleaner’.

Here is a modern reconstruction of this ditty. The text of the ballad as follows:

Be Peace!

Ye make me spill my ale!

Now think ye this is a fair way?

Let go! I say! Straw for your tale!

Leff work a twentyadevil away!

Ween ye that ev’rybody list to play?

Abide a while! What have ye haste?

I trow for all your great affray,

Ye will not make too huge a waste.

Come, kiss me! Nay! By God, ye shall!

By Christ, I nill, what says the man?

Ye hurt my leg against the wall;

Is this the gentry that ye can?

Take to give all, and be still then!

Now ye have laid me on the floor;

But had I wist when ye began,

By Christ,I would have shut the door.

The ‘rude’ version of this ballad appears later, in what is another pivotal part of Cromwell’s character development by Mantel, and the description of Cromwell’s murder of ‘eel boy’ (p.659):

But there is no watchman tonight, as you well know. When you issued out, Walter and his mates were an hour into strong ale. He’s a beast of a brewer, but he keeps back the best for his crew. And it’s Wilkin the Watch who sticks his face out of the room: ‘Drink with us, Thomas?’

He says, ‘I’m going to church.’

Wilkin retreats, withdraws his slack glistening face. From behind the door, rollicking song: By Cock, ye make me spill my ale

When he leaves to meet ‘eel boy’, Cromwell hears Walter and his friends from behind the alehouse door, singing By Cock, ye make me spill my ale… which is the first reference to the ‘rude’ adaptation of the ditty later performed by Henry.

In what follows the refrains from the ballad continue to permeate the narrative (p.660):

You walk, under the waning moon. Only when you sight eel boy do you break into a trot, an easy pace that will take you unwinded to your destination. When you enter the yard he is not in sight. But there is no one to stop you following him into the darkness, into the undercroft, where under deep vaulting, behind chests and boxes stamped with the devices of alien cities and their trading guilds, eel boy has burrowed in.

You think of the home you left. You wonder where Walter and his mates have got to with their song. With its refrains and variations they can draw it out an hour or more. Walter likes to take the lass’s part, squealing as she is backed against the wall: Let go I say …

Then the men chorus: Abide awhile! Why have ye haste? and mime pulling their breeches down.

Luckily, when they sing this song, there is never an actual woman in the room.

Down in the cellars your eyes have adjusted to the gloom. You want to laugh. You can hear the rasp of the boy’s breath. You move towards him, and you let him know that you know exactly where he is. ‘You might as well wave a flag,’ you call.

You halt. If you stand longer (and you have the patience) he will begin to cry. Beg.

Let go I say

After Eel Boy is murdered, and Cromwell is dragging his body along the floor, Mantel brings the ballad back again (p.661):

So you dragged eel boy, his red head bumping along, sedate. Your pace is necessarily slow: Abide awhile, why have ye haste? Outside, it is warmer than in the cellar. The street is empty, till you see the watchman, heading home. His walk is the purposeful sway of a man in drink, still hoping to pass as an upright citizen: ask him, and he’ll say he’s swaying like that just for fun. ‘Straight as a …’ the old sot shouts. He has baffled himself; he can’t think what is st’raight. ‘Put-an-edge-on-it! You’re out late.’

“He’s forgotten he saw you earlier. That he invited you to a bench at his song school.

Wilkin blinks: ‘Who’s yon?’

‘Eel boy,’ you say. No point pretending.

‘By Cock, he’s had a skinful! Taking him home? Good lad. Got to look out for your friends. Want a hand?’

Wilkin heaves, and vomits at his own feet. ‘Clean that up,’ you say. ‘Go on, Wilkin, or I’ll rub your head in it.’

Suddenly you are outraged: as if the only thing that matters is to keep the streets clean.

After he has left the boy, despite his temptation to curl up and lie down next to him, Cromwell goes back to the alehouse, where Walter and his boys are still singing the song (p.662):

When you get back, Walter and his boys are still bellowing. You are astonished. You thought it was three in the morning. You expected dowsed lights, shutters, padlocks. But there they are, still roaring away: Come kiss me! Nay! By God ye shall …

The door opens. ‘Thomas? Where been?’

You don’t answer.

Walter sounds as outraged as you were, when Wilkin fouled the highway. ‘Don’t you turn your back on me!’

‘Christ, no,’ you say. ‘He’d be a fool and short-lived, that did that.’

Walter raises his hand. But something – perhaps his own unsteadiness, perhaps something in your eye – makes him back off. ‘I’ll be right with you, lads,’ he shouts.

They’ve reached the part where they rape the maid. Walter will be required to imitate her cries. Now have ye laid me on the floor …

With this ballad adaptation, Mantel has drawn attention to the superficiality of the adaptation of Cromwell himself during his rise to power, and his elevation from a world of bawdy rhymes to the royal court. But Mantel is emphasising how parts of Cromwell haven’t really changed. He still carries the knife he used, eventually handing it to his servant Christophe after a near murderous encounter with Norfolk (p.780).

The night before Cromwell’s execution, echoes of this moment return (p.867):

He thinks he sees the eel boy looking at him from the corner of the room. Shog off, you streak of piss. He says.

In these final pages we also see another way that Mantel has illustrated the complexity of Cromwell’s character through popular song and where music, verse and prayer combine (p.872)

After the silence of the Bell Tower, he feels he is on a battlefield, moving to the beat of the drum: boro borombetta …

Scaramella to the war is gone …

Now the pages of the book of his life are turning faster and faster. The book of his heart is unscrolling, the lines erasing themselves. Between his prayers run the lines of verses, which are by Thomas Wyatt.

His heart thuds as if it will break out of his chest. Behind him, another drumbeat, rat-tat-tat… He swivels his head, distressed, to the source of the racket, a drum in the crowd. The guard close in, as if to block his view. Why? Do they think it is a signal? Rat-tat-tat: do they think he hopes to be rescued?

Scaramella fa la gala …

With this Italian song (and you can hear a reconstruction here) Cromwell is returned to another pivotal moment of his life, his arrival at the Frescobaldi counting house, which was told in the first part of this story – Wolf Hall (p.206):

He saw a young boy – younger than him – on hands and knees, scrubbing the steps. He sang as he worked:

‘Scaramella va alla guerra

Colla lancia et la rotella

La zombero boro borombetta,

La boro borombo …’

‘If you please, Giacomo,’ he said. To let him pass, the boy moved aside, into the curve of the wall. A shift of the light wiped the curiosity from his face, blanking it, fading his past into the past, washing the future clean. Scaramella is off to war … But I’ve been to war, he thought.

He had gone upstairs. In his ears the roll and stutter of the song’s military drum. He had gone upstairs and never come down again. In a corner of the Frescobaldi counting house, a table was waiting for him. Scaramella fa la gala, he hummed. He had taken his place.

This moment was so formative in Cromwell’s life, Mantel makes it pivotal to his last moment:

‘He kneels. He makes his prayer. Drumbeats. La zombero boro borombetta … Blink of red.’

Further reading:

English Broadside Ballad Archive: https://ebba.english.ucsb.edu/

Jenni Hyde, Singing the News: Ballads in Mid-Tudor England (London: Routledge, 2018)

Chris Marsh, Music and Society in Early Modern England (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010).

Una McIlvenna, ‘When the News Was Sung: Ballads as News Media in Early Modern Europe, Media History 22 (2016): 317-333

Emilie K. M. Murphy, ‘Music and Catholic Culture in post-Reformation Lancashire: piety, protest, and conversion’, British Catholic History 32 (2015): 492-525

Tessa Watt, Cheap Print and Popular Piety, 1550-1640 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991).