On the outskirts of Liverpool is Speke Hall, which was built from 1530-1598 by the Norris family and is now in the ownership of the National Trust. The fabric of the hall contains many visual and acoustic conundrums. In the Tudor period, there was a fashion for building riddles and curious devices into buildings, but the riddles of Speke Hall connect to the Catholic faith practiced by the family.

The freedoms and restrictions placed on Catholics in early modern England would ebb and flow in accordance with political pressures. From November 1569 until January 1570, a Northern Rebellion led by Catholic noblemen endeavoured to depose Elizabeth I and place Mary Queen of Scots on the throne. Misjudging the moment and attempting to support the uprising, in February 1570, the Pope issued the Bull Regnans in Excelsis, which excommunicated Elizabeth and freed her subjects from their oaths of loyalty. Catholics had always been treated with suspicion at this time in Protestant England, but this act gave the authorities justification for enacting more punitive measures and brutal punishments. Harbouring Catholic priests was a treasonable offence and many notable Catholic families installed priest holes in their homes to offer protection from arrest. The main builder of priest holes was Nicholas Owen (c.1562 – 1606) who designed many of these hidden crevices before he was caught and tortured to death in the aftermath of the Gunpowder Plot. These hidden tiny rooms were usually accessed via narrow ladders and were where priests could hide if the property was searched: each priest hole was built with the fabric of the building in mind and no two priest holes are identical.

Speke Hall has one known priest hole, but built into the house are also modes of surveillance to enable the household to determine whether unexpected visitors were friends or foes: above the Great Hall, there is a hidden whispering gallery to enable listeners to hear what is said below; above the main entrance is a hole cut into the eaves where people could eavesdrop on whoever came to the door as the enclosed courtyard amplified the sounds of their voices; there is also a spyhole cut into a chimney and overlooking the driveway to enable people approaching the Hall to be seen. These are all elements of the Norris family’s attempts to keep themselves safe through surveillance, but they are also parts of the riddle of the house and write the body of the owner into the body of the house. Since being found harbouring a Catholic priest could lead to fines, imprisonment and even execution, hiding the body of a Catholic priest in the body of the house was a way to keep all the bodies in the house safe. Whereas some Tudor houses incorporated riddles to present visual puns, for the Norris family, riddles and devices are part of the relationship between home and owner where the home protects the owner.

The overmantel in the Oak Parlour continues the riddle by visually depicting the Norris family. In the middle is a carving of Sir William Norris (1501 – 1568), who began construction work on the building in 1530. He is flanked by Ellen Bulkeley, whom he married in 1521, and Anne Myddleton (d. 1563), whom he married after Ellen’s death sometime before 1535. Ellen is depicted as holding rosary beads and Anne has no visible signs of being a Catholic: we have Ellen, William’s wife before Henry VIII broke with Rome via a series of legislation that culminated in the Act of Supremacy (1534) and an Act Against the Pope’s Authority (1536), displaying her Catholicism and Anne, William’s wife from around the time of this break, with a book next to her – perhaps gesturing to sola scriptura (by scripture alone), the Protestant belief that scripture had authority over the church.  The Treason Act of 1534 made treasonous denying any of the monarch’s titles, including the title of Supreme Head of the Church: in recognising the Pope as the divine authority on earth, Catholics were therefore guilty of treason. The carving might represent an anxiety to conceal the family’s Catholic faith, or it could indicate that Anne had conformed and converted to Protestantism. In 1571, Sir Thomas Stanley, second son of the Earl of Derby, was implicated in a plot to free Mary Queen of Scots from her imprisonment at Chatsworth. One of the questions William Cecil, Lord Burghley and chief adviser to Elizabeth I, sent to form part of Stanley’s interrogation asked, ‘What images were set up of late in the chapel of Lathom [i.e., Stanley’s private chapel], by whose commandment?’.1 For Burghley, the visual imagery associated with Catholic devotion might offer clues to uncover treasonous intent. In this context, the overmantel at Speke is not a neutral carving of a family’s genealogy, but instead plots the Reformation and hints at the Catholic secrets of the house.

The Treason Act of 1534 made treasonous denying any of the monarch’s titles, including the title of Supreme Head of the Church: in recognising the Pope as the divine authority on earth, Catholics were therefore guilty of treason. The carving might represent an anxiety to conceal the family’s Catholic faith, or it could indicate that Anne had conformed and converted to Protestantism. In 1571, Sir Thomas Stanley, second son of the Earl of Derby, was implicated in a plot to free Mary Queen of Scots from her imprisonment at Chatsworth. One of the questions William Cecil, Lord Burghley and chief adviser to Elizabeth I, sent to form part of Stanley’s interrogation asked, ‘What images were set up of late in the chapel of Lathom [i.e., Stanley’s private chapel], by whose commandment?’.1 For Burghley, the visual imagery associated with Catholic devotion might offer clues to uncover treasonous intent. In this context, the overmantel at Speke is not a neutral carving of a family’s genealogy, but instead plots the Reformation and hints at the Catholic secrets of the house.

This carving thus presents us obliquely with one of the ways in which devotion was understood through material objects, but the overmantel also gestures to the complicated relationship William had with his faith: William held a number of offices, including Sheriff of Lancashire (1544-5) and Mayor of Liverpool (1554-5) and he sat on the council of Edward Stanley, 3rd Earl of Derby (by 1555), all of which would have required him to swear oaths of loyalty to the Crown and established church. Indeed, in 1536 he supported the Earl of Derby’s efforts in quelling the Pilgrimage of Grace – a predominantly northern rebellion against Henry VIII’s break with Rome and the Dissolution of the Monasteries. Despite William’s clear signs of conformity, shortly before his death he was formally reconciled with Rome. William’s descendants then became (and became associated with) noted Catholic recusants (people who refused to attend Church of England Services) until the Norris family converted to Protestantism in the late seventeenth century. William and Anne’s granddaughter, Emilia, married William Blundell of Little Crosby, who describes his experiences of being imprisoned for harbouring priests in the 1590s in his commonplace book. Emilia too was interrogated by the Bishop of Chester and imprisoned at Sefton and Chester. The Norris family thus became part of the wider network of Catholic gentry later in the sixteenth century, but William Norris and his two wives present us with a puzzle: William may have been a church papist, somebody who had all the outward signs of conformity while secretly practising Catholicism, or he may have dabbled with Protestantism before returning to the Catholic faith. The overmantel presents us with a conundrum as to whether it plots religious conversion or concealing faith as a way to protect the family from stringent penalties.

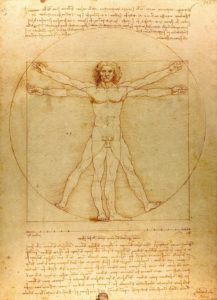

The fabric of Speke Hall thus hints at – as much as it conceals – the devotional practices of the household, and yet it also says something about how the Tudors understood architecture and the relationship between buildings and bodies. Renaissance building design increasingly looked to Vitruvius, a Roman architect who is considered to be the father of architecture. His ten books on architecture were rediscovered towards the end of the fifteenth century and his observations that architecture must imitate nature and that buildings should be proportioned around a well-shaped human body influenced Leonardo da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man (c. 1492). Fundamental to this is an idea of symmetry in the body and in the wider universe: there is a sense of harmony and order through the way in which all things connect to each other. But Vitruvius was not only interested in proportionality in terms of how buildings looked, he was also interested in proportionality in relation to how they sounded. Vitruvius believed a building had to be designed with stability, utility and beauty in mind, and this carries through into Tudor architecture. The first architectural treatise written in the English language, John Shute’s The First and Chief Grounds of Architecture (1563), draws heavily from Vitruvius and shares Vitruvius’ interest in architectural acoustics. Writing on music, Shute states:

Musicke […] is verie necessary for an Architecte, for these causes must he haue, as it were a foresight in it, that therby the principall chambers of the house, shuld with suche order be made, that the voice or noyse of musicall Instrumentes, should haue their perfaict Echo, resounding pleasauntly to the eares of those that shalbe heares therof, as also the Romaines, vsed in all their pallaces & for many other necessities therunto belonging, of the which Vitruuius, maketh further demonstration, as the refreshing of the Melancolicke mindes, which ar alwaies trauailing for further knowlaige. (Shute, sig. B4r)

According to humoral theory, which underpinned medical knowledge in the sixteenth century, scholars were prone to melancholy and Shute is here suggesting that music can help the mood of someone who is of a melancholic disposition. His discussion broadens out to focus upon the perfect echo of the room and how the echo of the room connects to the way in which people listen to and hear words and music. There is a sense of order and proportionality in terms of acoustic space that is worth thinking about in relation to how sound reverberates around the courtyard at Speke Hall and how the whispering gallery and the Great Hall form a sonic environment that enables people to overhear conversations. In amplifying sound, the body of the house becomes an extension of the human body. We can see how architectural tracts used the metaphor of the body to understand architectural space, but the human body is also fundamental to understanding the body of the house. During the course of the network, we will be working with Speke Hall to understand better the acoustic environments of the Hall and how this connects to the family’s Catholicism. The National Trust has commissioned two unique sound installations from sound artist, Serena Korda, which explore the historic soundscapes of the Hall and we will be working with electroacoustic composer, Peter Falconer, to explore the soundscapes of recusancy.

1 Hatfield Papers MS 157, fol. 136.

Watch this space for Peter Falconer’s soundscape. Further details of Serena Korda’s sound installations and downloads of the Bell Tree and Under the Rose can be found via the National Trust’s website. Serena’s soundscapes can be experienced at Speke Hall until July 2019.

Feature image: Speke Hall – View From the Bridge ©National Trust/Andrew Butler

Further Reading:

Bossy, John, The English Catholic Community, 1570-1850 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1976).

Davidson, Alan, ‘Norris, Sir William (1501-68) of Speke, Lancs.’ History of Parliament Online.

Haigh, Christopher, Reformation and Resistance in Tudor Lancashire (Cambridge: Cambridge Univeristy Press, 1975).

Panofsky, Erwin, Meaning in the Visual Arts (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1970).

Questier, Michael, Catholicism and Community in Early Modern England (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006).

Shagan, Ethan H., Popular Politics and the English Reformation (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003).

Shute, John, The first and chief groundes of architecture vsed in all the auncient and famous monymentes with a farther & more ample defense vppon the same, than hitherto hath been set out by any other (London, 1563).

Walsham, Alexandra, Church Papists: Catholicism, Conformity and Confessional Polemic in Early Modern England (Woodbridge: Boydell, 1993).

Walsham, Alexandra, Catholic Reformation in Protestant Britain (Farnham: Ashgate, 2014).

Wittkower, Rudolf, Architectural Principles in the Age of Humanism, 5th edn (London: Academy Editions, 1998).