In this period of social distancing, videos of people singing together from their balconies appear everywhere on our social media. Some balconies house better performers than other balconies, but it doesn’t really matter whether your voice sounds like Cecilia Bartoli’s or whether you’ve only ever sung in the shower. What matters is that the singing breaks through the social isolation. These videos thus testify to the power of music to create and maintain communities.

In times of crisis, we become newly aware of our need for physical connectedness. Even though it is possible to stay in touch with other people through social media whenever we want, we also feel the need to gather not only virtually, but also physically – even if such gathering has to take place at the distance between one balcony and another. But why, once we’re on our balconies, do we start singing?

The Coronavirus crisis is not the first crisis that people have had to live through, and it is not the first crisis during which people have started singing. In times of social agitation, political turbulence or natural disasters, people have sung songs to create feelings of togetherness and solidify their social group. There are many examples of this to be found in the early modern period. In the sixteenth century, for example, at the time of the Reformation in Europe, singing played an important part in the construction of the new Protestant religious community. On the other end of this conflict, Catholics in Elizabethan England sang to maintain their community in the face of persecution. Those sentenced to death even continued singing at the stake in order to assert their religious identity and shape their martyrdom within a religious tradition.

Furthermore, many national anthems were first performed in times of crisis. Take, for example, the French Marseillaise, which started as a protest song in a political conflict, then went on to be used to define a new nation after the transformations caused by the French Revolution, and is now still used to represent and strengthen French national identity. The collective singing of such a song confirms, time and time again, the community that is connected to that song.

The social isolation that has today been imposed on many of us, and which singing can help us resist, can be compared to other situations as well, including the experience of (in)voluntary migration. Through music, migrants have often tried to keep a connection with their original community. Just think of the music performed in many Irish pubs all over the world, or of the gospel choirs that maintain a worldwide religious community through singing. Enslaved African people started singing spirituals to stay connected to a community of fellow sufferers and draw strength from the knowledge of a shared faith.

Exile offers another historical ‘equivalent’ to our present moment. At the end of the eighteenth century, many Dutch revolutionaries had to flee the Dutch Republic after a failed uprising. From their new homes in France, England and Germany they kept on singing the songs that had driven their political movement. This helped to hold their scattered community together until they were able to successfully set in motion the Batavian Revolution and their return to the Netherlands.

In all these examples, singing is what keeps people connected. The voice is the one instrument that most people have access to, and everybody can sing to some degree. From the beginning of our history, music has helped us to create feelings of community, and to maintain collective identities. Some anthropologists even believe that music has played a central role in human evolution and in our survival as a species because the collective identities that are created when we make music together form the basis of the physical social groups that are essential for our existence. The bodily experience of making music together, of singing together, in which we act in synchrony, creates feelings of unity and togetherness. In times of crisis, we depend on the solidarity within the groups that we are a part of – our families, friends, neighbours; our local and national communities – not only to survive, but also for emotional, practical, and financial support (and supplies of toilet paper!).

My neighbours in Rome singing Bella Ciao ❤️?? pic.twitter.com/gu1NqNjlHQ

— Jessica Phelan (@JessicaLPhelan) March 13, 2020

However, singing collectively reaches further than our physical communities. This is something that is illustrated by the videos of Italians, who were the first to be seen singing from their balconies. The responses to these videos show us that their singing did not only connect the people in the Italian cities and people from many other countries were also moved by this act. Even though non-Italians may not have known the songs that were sung, music is such a universal phenomenon that we don’t need language to understand what a song expresses. Even if most people won’t be aware of the historical connotations of a song like Bella Ciao, they will still immediately sense the belligerent character of this song and feel strengthened by it. This way, music not only creates embodied communities, it also creates imagined solidarity: even if we cannot actually be physically near them, we know that people in many other places are going through the same thing as we are.

A difficult situation like the COVID-19 pandemic thus shows us what we as humans return to when we feel vulnerable: musical ways of staying connected. It underlines the importance of social groups and the importance of music for maintaining such communities in difficult times. Even though we will not be able to go out for a while, we can keep singing because while singing is admittedly contagious, it does not transmit the Coronavirus. Therefore, stay safe and keep singing!

Renée Vulto is a musicologist and cultural historian, based at Ghent University.

This piece is a translation and adaptation of a piece originally published in Dutch on the historical blog Over de Muur (https://overdemuur.org/zingen-in-tijden-van-corona/)

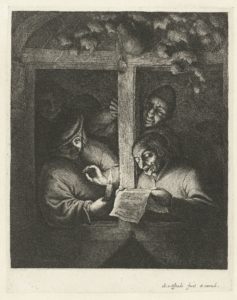

Feature image: ‘Merry Company on a Terrace‘ c. 1670 by Jan Steen

Further Reading:

- Cornelis van der Haven, ‘Singing the Nation: Imagined Collectivity and the Poetics of Identification in Dutch Political Songs (1780-1800)’, Modern Language Review 111 (2016): 754-774.

- Lotte Jensen, ‘“Disaster upon Disaster Inflicted on the Dutch”. Singing about Disasters in the Netherlands, 1600-1900’, BMGN – Low Countries Historical Review 134 (2019): 45-70.

- Laura Mason, Singing the French Revolution: Popular Culture and Politics, 1787-1799 (Cornell University Press, 1996).

- Jan-Friedrich Missfelder, ‘Akustische Reformation: Lübeck 1529’, Historische Anthropologie 20 (2012): 108-121.

- Emilie K. M. Murphy, ‘Musical Self-Fashioning and the “Theatre of Death” in Late Elizabethan and Jacobean England’, Renaissance Studies 30, (2016): 410-429.

- Thomas Turino, Music as Social Life: The Politics of Participation (The University of Chicago Press, 2008).