Early Modern Europe was an aural world. Despite the invention of print and the rise in literacy, speech was still the main form of communication: it was at the heart of religious worship and legal practice. In a world based around the spoken word, what about those who struggled to hear or who couldn’t speak?

Prelingually deaf men, women and children (who contemporaries called ‘deaf and dumb’) were theoretically excluded from many important aspects of life in Early Modern Europe. Since prelingually deaf people could neither hear nor show their consent through speech, they were often seen as being legally like infants. This meant they could not marry or make a will, and early modern priests worried about whether prelingually deaf people could enter heaven. A stumbling block for many was the assertion by St Paul that ‘faith comes by hearing’ and ‘by the mouth, confession is made unto salvation’: how could deaf men and women either come to know God or perform the necessary sacraments?

It was a problem that troubled Catholics and Protestants: they worried about how to communicate with deaf and deafened people, and how to help those same people to take part in Church sacraments. Dominican Friars – who had a tradition of using their fingers to remember parts of their sermons – introduced finger spelling to help men and women make their confessions when speech was not possible. In the following centuries, a Benedictine monk, Pedro Ponce de Leon, taught deaf children to lip read and so to communicate by ‘speaking’ in Spanish. As a result, deaf children of Spanish noblemen were able to make wills, inherit their parents’ wealth, make confession and attend Church services. Pedro Ponce de Leon’s efforts were carried on in Spain by Juan Pablo Bonet, who published a guide to teaching deaf children to ‘speak’: Reduccion de Las Letras (1620).1

These early efforts at Deaf Education prefigured the Oralist movement of the nineteenth century, when prelingually deaf children were encouraged to speak and lipread in their native languages rather than using sign language, but at the same time as Spanish children were being taught to speak vocally, elsewhere in Europe sign language was being recognised as a valid alternative to oral speech.

In seventeenth-century Geneva, the Catholic Bishop, Francis de Sales prepared a prelingually deaf boy, Martin, for communion using sign language. Martin ‘could express by signs good and evil thoughts of the mind, perfect and imperfect consent of the will, and the difference between mortal and venial sin’. In seventeenth-century Protestant England, it was reported that the ‘gestures and zealous signs’ of a prelingually deaf gentleman, Edward Gostwicke, ‘’procur’d and allow’d him admittance to sermons, to prayers [and] to the Lord’s supper’. Increase Mather recorded a prelingually deaf woman taking the Eucharist in colonial America, writing that those ‘born, or by any accident made Deaf and Dumb … [who are] able by signs (which are analogous to verbal expressions) to declare their knowledge and faith; may as freely be received to the Lords supper as any that shall orally make the like profession.’

Language, of course, relies on mutual understanding and so for the signs to have a legal status they needed to be agreed and accepted by all the parties involved. Two marriages in early modern England show the problems – and benefits – of using sign language as an alternative to oral speech. In 1618, a prelingually deaf man, Thomas Speller, married Sara Earle after getting permission from the chancellor of the diocese of London and the Lord Chief Justice, who agreed in advance the signs that Speller would use to show his consent. Fifty years earlier in Leicestershire, another prelingually deaf man, Thomas Tilsye, married using sign language. To show his willingness to marry his bride, Ursula Russell, he enacted elements of the wedding ceremony: ‘first, he embraced her with his arms, and took her by the hand, put a ring upon her finger, and laid his hand upon her heart, and held his hands towards heaven; and to show his continuance to dwell with her to his life’s end, he did it by closing of his eyes with his hands, and digging out of the earth with his foot, and pulling as though he would ring a bell’.

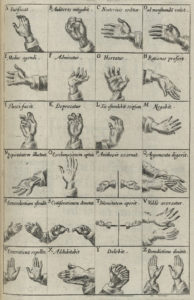

Tilsye’s marriage shows the power of sign language, and visual kinetic languages were increasingly seen as a valid alternative to oral speech – and not just for deaf people. The British Civil Wars revealed the limitations of speech in political discourse, and from the mid-seventeenth century there was a growing interest in manual languages as an alternative to vocal speech. In 1644, John Bulwer published a handbook of hand signs, Chironomia & Chirologia, in which he argued that physical gestures were a ‘language more natural and significant’ than oral speech. John Bulwer later explored the importance of sign language for deaf people but like other linguists working in this field, he argued that sign languages had benefits for everyone. Sign language was not just a substitute for speech, but captured truths that were beyond human words. Bulwer argued that sign language was God-given to hearing and deaf alike: it was the ‘Dialect of his Divine hands’. Early modern Europe may have been an aural world but it was a visual one too, and this increased interest in sign language helped to assimilate deaf and hard of hearing people into a world of speech.2

1 Juan Pablo Bonet, The Simplification of the Letters and the Alphabet and Method of Teaching Deaf-Mutes to Speak, trans. H. N. Dixon, (London, 1890).

2 John Bulwer, Philocophus Or the Deaf and Dumbe Man’s Friend (1648)

Rosumud Oates is Reader in Early Modern History at Manchester Metropolitan University

Feature image: John Buwler, “Chirologia, or The Natural Language of the Hand” (1644), titlepage. Credit: Folger Shakespeare Library