‘Close your eyes, it’s the 17th century and you are awaiting a sermon at the York Minster. Who is speaking? How are they speaking? What are they saying? What does it sound like? What sounds can you hear in the background? These are some of the questions that the field of historical soundscapes studies reflects on.

With such a number of questions, it is not surprising that the exploration and the recreation of historical soundscapes involves a great variety of disciplines.[1] Scholars have, for example, reflected on sound sources in different historical periods, on the environments in which said sources were experienced and on how the experience of listening influenced day-to-day life. The workshop ‘Early Modern Global Soundscapes’ held in York in January 2019 highlighted how stimulatingly varied the field of historical soundscapes studies can be. The analysis of a single event, let’s say a speech in a cathedral, involves, for example, studying the preacher/speaker themselves, as well as the text, the particular occasion and the sociological context in which it took pace and, last but not least, the space where it took place. The Virtual Paul’s Cross Project’s recreation of Donne’s Gunpowder sermon in November 1622 is an excellent example of this.

But, why are cathedrals a focus of interest? Cathedrals and churches were central to cities and communities in Early Modern Europe, playing a key role in their soundscapes. From the outside, their bells represented one of the most characteristic elements of medieval soundscapes,[2] and their interiors were key public venues for community events. Furthermore, cathedrals are “live buildings” that change over time along with the society and their culture to fit their needs. At the same time, people adjust their behaviour to suit the particular environment that these architecturally complex buildings create for them, not only visually, but also sonically. How these performance spaces and their particular acoustic behaviour may have shaped the sonic events that the listeners experienced in them over time is the focus of our research.

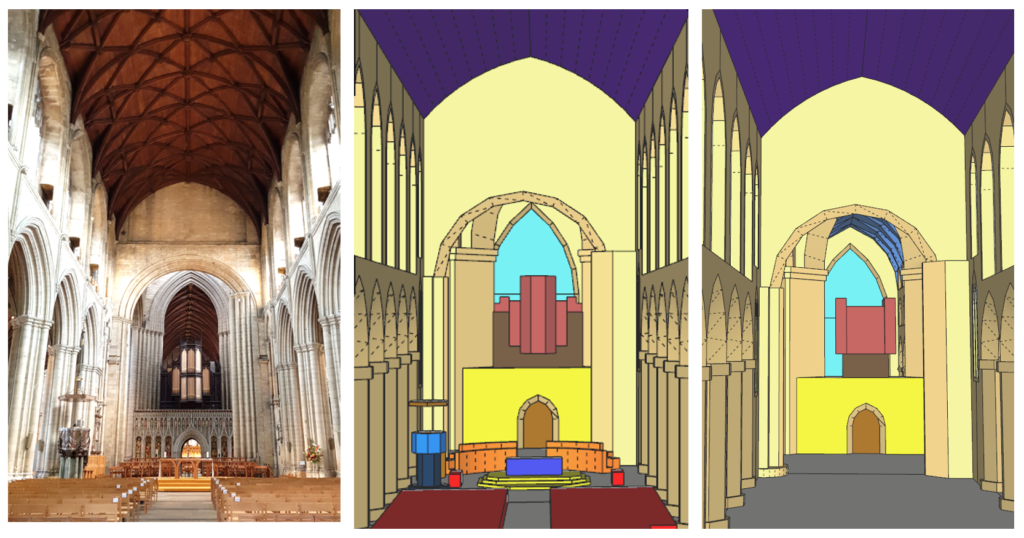

Cathedral Acoustics is a project that investigates the acoustic behaviour of a sample of English cathedrals: the cathedrals of Bristol, Ely, Ripon and York. We combine in-situ measurements and simulation techniques to analyse their acoustics in depth. The signals recorded during the measurements provide valuable information about how the space performs in terms of sound nowadays, and serve to preserve their sound as part of their intangible heritage. Additionally, the acoustic simulations give us the possibility of assessing the impact of the most acoustically significant architectural changes that these cathedrals experienced over time, in an attempt to understand the role that the acoustic environment of cathedrals played in the sonic events that took place in their interiors throughout history. Thanks to these techniques, we are able to analyse how the acoustics of Bristol cathedral shaped sermons given by Edward Chetwyd in 1612, when its nave remained unbuilt; how Ripon cathedral’s choir sounded before and after the remarkable architectural reformation by Sir Gilbert Scott took place at the end of the 19th century; or the acoustical features of the Lady Chapel of Ely Cathedral when the space was fully furnished to be used as the Holy Trinity Parish Church, from 1566 until 1938.

Although we, as acousticians, strive to generate meticulous re-creations of the past based on historical evidence and using cutting-edge technology,[3] creating an appropriate acoustic historical model of a cathedral is indeed, a challenge. The 3D interior model must be carefully simplified to perform properly in the simulation software, but, how to simplify such huge, complex and full-of-detail buildings without losing their geometrical properties? Furthermore, the acoustic characteristics of their finishing materials have to be well estimated in the model in order to achieve an accurate representation of the acoustic behaviour of the space within the simulations. But, how can we estimate the acoustical impact of elements such as organ pipes, or a rood screen? These uncertainties make the use of approximations inevitable. So, in view of these uncertainties, we take the acoustic measurements performed on-site as a reference to validate the acoustic model of the cathedrals in their current state.

So, how does it work? We use sine sweep signals to determine the room impulse responses (RIR) of relevant source-listener positions in the cathedrals, for example when the source is placed at the High Altar and the receiver at representative points throughout the congregation area, as can be seen in figure 2.

Each RIR provides information on the components of the sound arriving at the listener at each reception point, which are the ‘direct sound’, the ‘early reflections’ and the ‘reverberant sound’. In other words, each RIR describes how the space changes, in terms of sound energy, the original sound emitted by a source located at a certain position in the room. Those signals are used to extract information about reverberation, speech intelligibility, music clarity and spatiality.

We then start an iterative process. We test the simulation model and modify it, by changing the simplifications assumed and/or the acoustic properties assigned to the surfaces until we can ensure that the results we get with the simulation are comparable, in terms of sound perception, to those obtained with the real measurements. The aim: for reality and simulation to be as similar as possible.

Once the current acoustic model is validated, we carefully modify it to better understand how the building performs in terms of acoustics and also to recreate past conditions. This methodology is broadly described in our journal paper on the acoustics of the remarkable Chapter House of the York Minster.[4]

The simulated room impulse responses are the basis to generate auralisations able to provide a plausible representation of the aural environment of each space at a particular point in history. An auralisation is the process by which a dry recording (captured in a reflection-free environment such as an anechoic chamber) is modified to acquire the acoustic properties of a space, so that, upon listening to it, you are virtually transported to that place.

The findings of this work are not only applicable to the study and preservation of the acoustics of English cathedrals. They are also crucial to the recreation of indoor soundscapes of other historical spaces, helping us further our knowledge of individuals’ auditory perception/s in Early Modern England.

Lidia Álvarez-Morales is a Postdoctoral Researcher and Mariana Lopez is Senior Lecturer in Sound Production and Post Production, both based in the Department of Theatre, Film, Television and Interactive Media, University of York.

Cathedral Acoustics project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Sklodowska-Curie grant agreement No 797586. To find out more about the project, see www.cathedralacoustics.com.

Acknowledgement:

We greatly appreciate the collaboration of the authorities and the staff of all the cathedrals involved in the project; the invaluable collaboration of researchers Angel Alvarez-Corbacho and Pedro Bustamante, both from the TEP130 research group of the University of Seville, with the acoustic measurements and modelling; the kind and indispensable collaboration of the AudioLab of the University of York; and last but not least, the help from all the volunteers who have participated in the different phases of this project.

Works cited:

[1] https://emsoundscapes.co.uk/listening-to-soundscapes/

[2] https://emsoundscapes.co.uk/bells-bells-bells-a-medieval-soundmark/

[3] Mariana Lopez, ‘Heritage Soundscapes: Contexts and Ethics of Curatorial Expression’, in The St. Thomas Way and The Medieval March of Wales, ed. Catherine A. M. Clarke (York: ARC Humanities Press), chapter 5

[4] Lidia Álvarez-Morales, Mariana Lopez & Angel Álvarez-Corbacho, ‘The Acoustic Environment of York Minster’s Chapter House’, Acoustics, 2 (2020):13-36. https://www.mdpi.com/2624-599X/2/1/3/htm